Kutch Folk Music thrived until 1970’s. Folk Musicians back then enjoyed great respect & following in their villages.

From 1970’s Kutch’s village economies moved from localized to non-localized. In this change, traditional practices like Folk Music, which do not have direct economic value associated with it, took back seat. As a result, the Folk artists have lost respect and demand for their skill among the villagers, which has led to a decline in number of artists passing on their knowledge and heritage to the next generation.

What Changed so much for the Kachchh Folk Music Ecology in the Last Few Decades?

Kachchh Ecology until 1970’s – localized economy and self-sustained.

“In the past there was freedom and leisure to pursue our creative folk arts – be it embroidery or music. And our audience also had the leisure to appreciate and participate in these recitals. The mahul (environment) at that time sustained both our lives and music. ” – Meetha Khan, Waai Artist

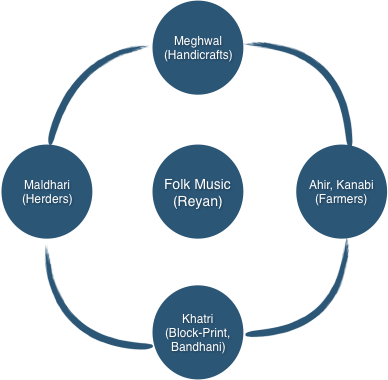

Till 1970’s the Kutch economy was not dependent on external markets or influences. Everything was produced and consumed locally. Every family had a certain role to play.

And only so much was produced that would take care of the local needs – farmers producing the grain and cotton crop to exchange it with pastoralists for milk and wool products. And farmers and pastoralists providing cotton and wool yarns to the weavers to make fabrics. Which then go to Khatris for dyeing. Similar roles were played by potters, leather artisans etc.

Everything and everybody in a village were connected. During these times, every fortnight Reyans were held where all the villagers gather to share their stories, problems and listen to folk music and folk lore.

In this economy, culture played a prominent role. And so at that time, the Folk Musicians of Kutch were held at very high esteem and made sure their needs were taken care of by the society. Due to this localised economy, the artists, be it in craft or music, practiced highest form of art possible, without being concerned about financial security.

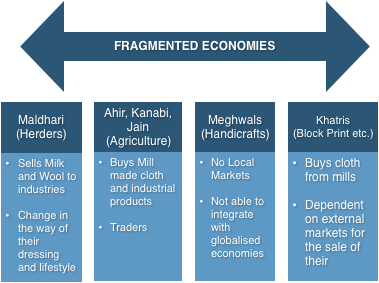

Rapid Changes in Lifestyle from 1970’s – Fragmented Economies and Linear Society Structure.

“Life in the past had certain coherence to it, despite hardships. It was wholesome – self-sustained and self-dependent. Our ancestors moved from one grassland to another with their livestock of cattle, sheep and camels. The livestock thrived and helped us sustain our homes and lives.

Today our lives are very much settled – no more nomadic. One of us in the family has to stay at home. We have to work hard to meet financial needs. We can no more migrate from grassland to grassland. Also Banni grasslands saw significant loss of its grass cover over the last 2 decades. Which means one has to walk far from their homes with their livestock to feed them. And when the rain-fall is not good, we have to buy grass for the live stock from Saurashtra (South Gujarat). Finally we have to reach the markets to sell the dairy products. Most of our time and energy goes in sustaining our lives and the live-stock. This the reason why Waai hasn’t passed on to the next generation – the youth in our community has neither time nor resources to practice Waai dedicatedly.” – Meetha Khan speaking on how the once thriving Waai Folk Music form is almost extinct today

Globalization and sudden change in life-styles and flooding of local markets with cheap industrial products led to the break-down of localised economies and with it broke the centuries old traditional partnerships that existed between the communities. With it, those involved with Folk Art and Crafts have to search for external markets for the sale of their goods. This gradually eroded the communication links that existed when the products were being sold within the local communities in their villages. This breakdown had a direct impact on the Folk Music – the Folk Musicians were probably the worst to be hit with the breakdown of localised economies.

Serendipity & Perseverance: In search of unforeseen paths

It’s not possible to take the society back to the old traditional roots of localised economic structures. In order to sustain the Folk Music of Kachchh today, we have to link up with the audience globally – Bharmal Sanjot, Trustee. Kala Varso

Post the 2001 earth-quake in Kachchh, majority of the artisans, particularly those in folk music, stopped their traditional forms. The reason being the long time-line it took for rehabilitation, and the lack of proper support to give them confidence to take up their tradition forms. Then with industrialization many artisans went to industries or construction work to make quick income.

Many development programs and interventions came up post the 2001 earthquake. But these programs were largely in-effectual and failed to create an independent identity to the artisans – the approach has been more like project-based. The folk music soon became a neglected area. After more than 10 years post earthquake, the Folk Musicians started feeling the need to start their own initiatives to tackle the problems they are facing instead of being dependent on others.

Kala Varso was born from this idea by the Folk Musicians of Kachchh coming together and having Reyans (discussions aided by Folk Music evenings in the villages) on how to sustain the Folk Music of Kachchh, not only in terms of the art form, but also to create sustainable economic model for the Folk Musicians of Kutch. Thus Kala Varso was formed in 2012. It is fully run by artisans. Even the board positions are occupied by the artists themselves. Culture, Folk Art and Stories & Legends, form a strong base for the Folk Music of Kachchh and so became the part of Kala Varso’s concept and mission.